Girt (by sea): Solstice, installation by artist Dr Lisa Anderson

We caught up with Dr Lisa Anderson, a contemporary artist who has had an illustrious career, including stints as artist-in-residence on Russian and Chinese science ships at the poles. Lisa’s work captures the essence of our connection with the Bay. Why is this important? Because to find ways of looking after our Bay means challenging ourselves to think differently, often in ways we’re not used to.

Listen to the interview here

Visit the Exhibition

‘Girt (by sea): Solstice will appear on the 21st of June in the gardens at Linden New Art 26, Ackland Street, St Kilda.

Interview with artist Lisa Anderson

We sat outside in the Veg Out Community Gardens in St Kilda today in lovely conditions by the sea and had a chat about her current project and its relevance to how we look after the Bay.

Dr Lisa Anderson outside her art studio in the Veg Out Community Garden, St Kilda.

Q. What made you into the artist you are today?

I've worked a lot in the Arctic and the Antarctic and in remote locations around the world looking at environmental issues from the landscape perspective.

I was awarded a Rupert Bunny fellowship in 2022 which is a fabulous thing and I was working on an exhibition I was pulling together called ‘Beguiling’ with images from the Arctic and Antarctic and realised that I'd done such a lot of expedition work on icebreakers but was hardly ever looking out at the sea. Then I suddenly found myself here, taking landscape photos looking out at the sea, and it was like we are girt by sea, as the saying goes, because to girt is an old-fashioned word that means to hold or to cradle.

Our border goes out for 200 nautical miles which means Australia is more sea than land so I called it girt by sea but I put ‘by sea’ in brackets and crossed it out because in in art language to cross something out means you're going blindly into it. In a way we're not girt by sea, we are the girt. To try to find those connections and look at what's happening around they just saw on a local front was kind of part of what I was doing

Q. Tell me about the 10 principles in your installation

I was looking at a thing called the 20 steps steps against tyranny which is a 1930s book about how you take a stand as a person and it had lines in it about being part of a civil society. I was thinking to appreciate our sea and to defend it and protect it and engage with it we need to be part of a civil society.

It's the most didactic piece in the whole show because I actually list the steps at the bottom of the video.

For instance, you can make up your own words for the sea so you're engaged with the place. There is a thing about words and I guess it goes back again to being a child. You make up words all the time. Making up your own words is childish but it's also something else because one of the things that I found to be quite important about words is that there's a lot of words we've forgotten. There’s 20 or 30 old english words meaning the water the wetlands and the sea. I think the other thing that became important in terms of play was looking at folklore because folklore is a form of playfulness too.

Q. How does contemporary art enable us to think differently?

It’s crossing to ideas of abstract thoughts. We've lost a diversity of language and over time, some words have less meaning meaning than they do now. We've also lost the stories and folk connection which means we're we're not as enriched as we once were.

Folklore is a broad brush way to explain the landscape and the animals. Like stories are about the moon disappearing. You know the moon does disappear for two nights a month, with the idea that Lunar needs to sleep. In terms of the sea almost every culture has got a mermaid of some sort, even Australian indigenous cultures, any culture that lived beside water has a mermaid.

The mermaid has to make a deal with life to be human which means they gain a soulbut lose immortality. It falls into a religious or spiritual kind of concept because they can live forever. It’s like extension of our own of psyche to imagine what we can't be or cannot understand.

In the enlightenment we decided we were separate from nature which has its drawbacks. But I’ve also spent time working in Iceland which have the mythical Huldufólk. There's a strong belief in them but when you're in the town they say, ‘I kind of see it as a bit like something for country folk’ but having said that, most of those people wouldn't deny there were Huldufólk, they just wouldn't admit there were Huldufólk!

I'm not sure how exactly, or how the installation is going to translate. But I think if you can become open to the belief in spirit of the earth, concepts like Huldufólk which exists everywhere, make sense. Colonial and post-colonial type cultures have lost a chunk of that. Our great-great-great grandparents left it behind in Denmark or Ireland or wherever.

Q. How does artwork compliment science?

Often in practical ways. I've seen artists turn formulas into something that can then be used in the real world. But I've also seen artists pull ideas out of science, stir them up with some folklore and almost like a pun, mesh two concepts together. It can be almost random. But it becomes not random because it's finding and seeking ways of presenting it.

Q. What do you hope people learn from your work?

There is a huge thing about what we take from the earth, what we buy, what we blow up. Or what we take from the sea ... and the gradual realisation that people live on a blue planet. We're more sea than anything.

You know, we still look at those photographs of our blue planet that were taken by Apollo 13. It takes us a long time to try and understand that. For instance, we're only just beginning to understand things on the seabed while we're busily destroying it.

I think just an idea to engage with what's here, to not separate yourself so much, to embrace the weather, to embrace the fact that we have a sea there that's really utterly amazing. It gives us something new and different every day. And trying to be still in a way that lets you feel the tides pull in your own salty blood.

Understanding is something but feeling can be as well. And I think in our world, feeling is considered a feminine quality and understanding is a male quality. And I think in the way that they're viewed, it's favouring one over the other, and I'm not sure they should be favouring one over the other. So it's a bit of feminism involved in that, and equality too.

But I think it’s also being playful enough to look at weird AI mermaids with bad fingers swimming up and down through jellyfish blooms. Some jellyfish are good, others bad, and I've just mixed them together. It’s getting people to play with the world as an abstract idea, rather than believing in mermaids, or being a mermaid.

It's not a big ask, it's just engaging.

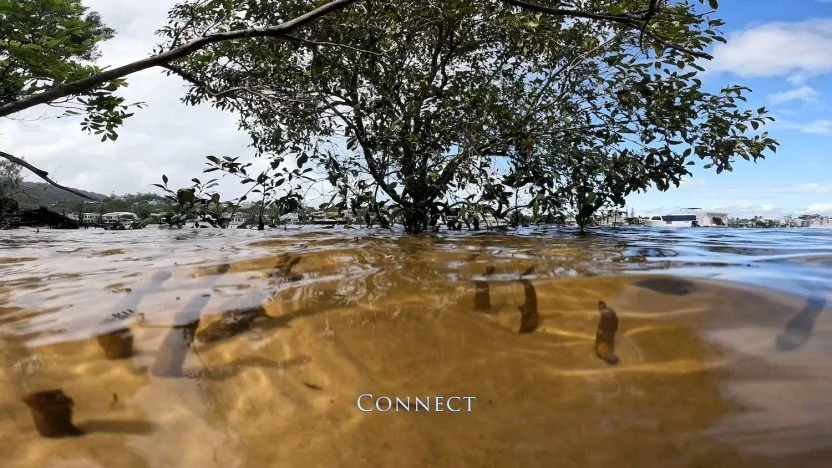

And, you know, thinking about the big words that I started to play with: connect and respect. Respect is one of those words that gets thrown around all the time. ‘You've got to respect me’ is the way we usually throw it about. But if you think about what we do to our planet, it's a lack of respect for oneself. You know, it comes back at you.

Q. Where can people find out more about your work, and see it?

Girt (by sea): Solstice is on for one night only, on the 21st of June (which is solstice night) between 6 and 9 o'clock in the gardens at Linden New Art 26, Ackland Street, St Kilda.

And visit my website, www.lisaanderson.com.au which has lots of different things about other current and past shows, as well as shows coming up.