Building community capacity for understanding, preserving and restoring Port Phillip Bay

Methodology Updates

Background

Community Stewardship

A growing number of people regularly use and depend on the Bay for business and recreation purposes. And while the value of an ecosystem can be measured directly (e.g. dollars earned from using natural resources), less tangible measures also relate to culture, health and wellbeing. These support the more direct benefits of lifestyles and livelihoods and are thought to be worth a lot more. Identifying these values means asking different questions of ourselves – ones that relate to how our personal values connect to ecosystem features.

To date, management decisions have largely been made by isolating people’s values from ecosystems and ecosystems from the economy. Considered separately, this forces a trade-off between ecosystems and the economy, overlooking the fact that 7-30 times more value might be achieved by preserving or restoring ecosystems if people are considered as part of the economy [1].

People as part of the environment

When it comes to the Bay’s ecosystems, it is possible to ‘have your cake and eat it.’ We can both secure our livelihoods and lifestyles, while protecting the underlying life support mechanisms.

To do this, however, means reintegrating people into the process.

We do already have a lot of knowledge about how both ecosystems and the economy function. However, we barely know anything about how people connect to the economy and ecosystems. Few have ever asked.

So, before we make any decisions that will change our Bay, the first step, is to integrate social and ecological (socio-ecological) knowledge so we have a more complete understanding of how our decisions affect the Bay and its people, together.

This is the justification for our program and where it starts.

The Program

The program ‘Building community capacity for understanding, preserving and restoring Port Phillip Bay’ aims to collect and integrate social values into a comprehensive model of how our Bay works.

It will use latest technology and a truly participatory approach, to assemble the evidence our community needs, to support decisions for all our futures.

The team involved in delivering this (see About Us) are renowned for their work, though to date, these projects are mostly done in less developed countries overseas. Because something akin to this has not been attempted in an urban setting before, it will take some time to build the process – before this, no-one has asked Victorians how they value their Bay.

Once we have a baseline, it is anticipated the process will be easily repeatable.

What follows is a more detailed overview of the steps involved.

The United Nations Environment Program says global investment in nature-degrading activities, outweighs investment in nature-based solutions thirty times. Meanwhile, it’s thought that restoring degraded land can yield 7-30 times more benefits for every dollar invested (Ding, H., et al., ROOTS OF PROSPERITY The Economics and Finance of Restoring Land. 2017). The European Union Nature Restoration Laws were adopted on this principle, that for every euro invested in land restoration, brings an economic return of EUR 8 to EUR 38 (European Commission, Nature Restoration Law: For people, climate, and planet. 22 June 2022 #EUGreenDeal).

Step 1.

Build a Conversation

The first step is to create a two-way knowledge-sharing process, engaging Bay users, allowing us all to learn about how the Bay works, and becoming part of the process. This is designed to accord with your individual time constraints and interests.

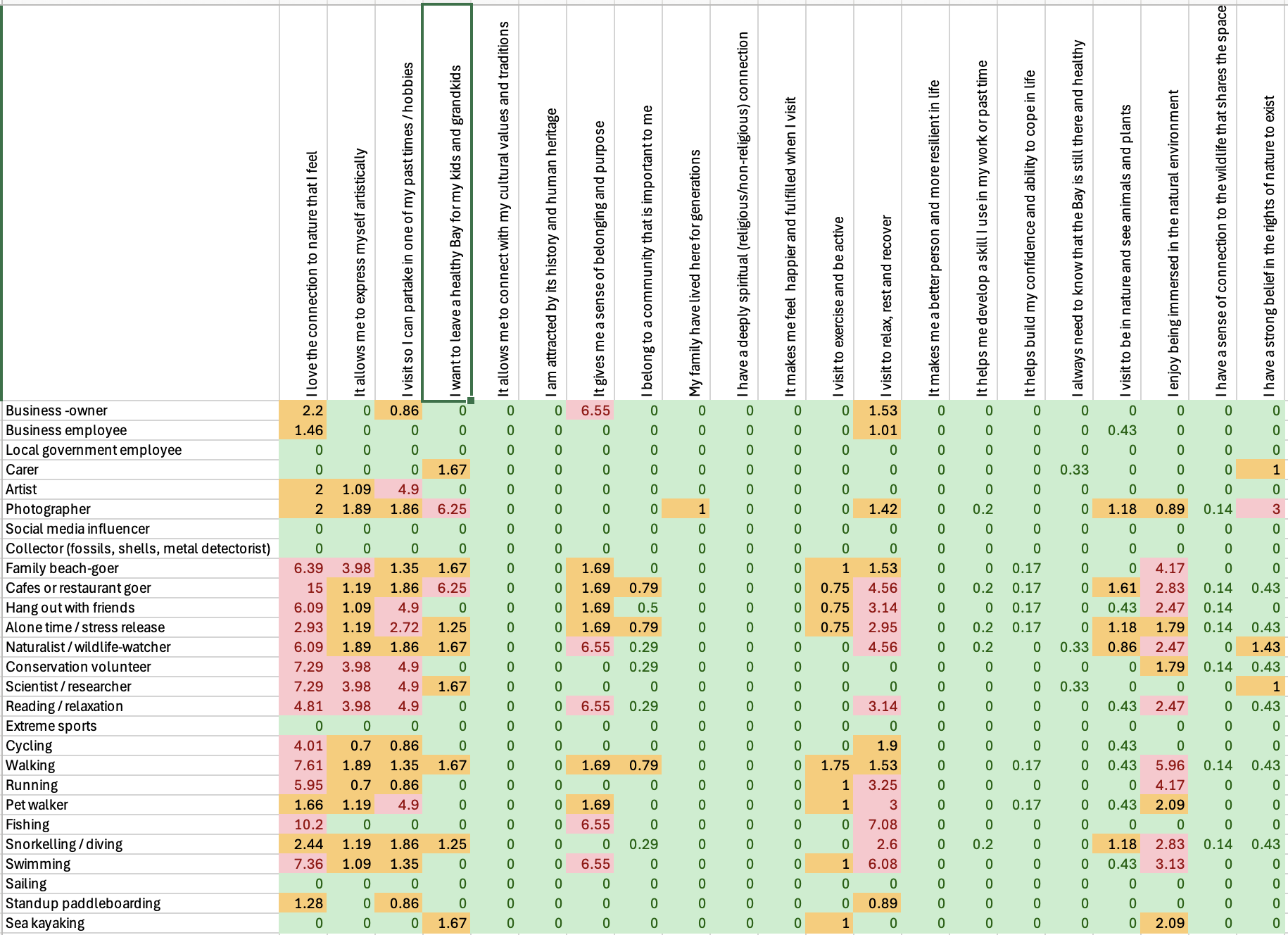

This is an exchange of knowledge, ideas, beliefs and values. Questions will be specifically relevant to a person / group of people and how their values and interests connect them to the broader socio-ecological system.

Careful attention is paid throughout, to ensure all voices are heard, so we achieve a democratic mix of inputs.

This approach moves our focus away from ‘problems’ (which tend to inspire conflict between people with different values) to one where we can look at how the overall system supports everyone’s values, and therefore, where there is commonality in our needs and the outcomes we all want to achieve.

Step 2.

The Socio-ecological Model

Socio-ecological means a mixture of social and ecological. It’s combining the human and environmental aspects of how the system works, so we can understand this better, and make reasonable decisions.

There are already frameworks that paint a picture of how threats and pressures cause impacts on the ecology-side. What we don’t know enough about are the social values and how these connect to the ecosystem.

The knowledge framework we build comprises millions of connections. The most significant effects flow through the web, emerging as predictions, about how the environment is affected, including the services it delivers to our lives e.g. clean water, clean air, recreation etc.

In this second step, we refine this model by importing and presenting the knowledge collected in Step 1. This tells us how ecosystem features connect specifically to the social values that Bay users consider most important.

We then prepare a series of focus-group workshops to refine these connections.

In this image, we can see all the community’s values represented on the right hand side. All the problems we face, from cost of living to health, are a result of this system falling into disrepair. By identifying critical pathways, we can focus on areas that matter to everyone. The objective is to turn the red lights green, by finding actions that benefit everyone.

Step 3.

Preliminary workshops

A series of workshops use the data presented in Step 2 as evidence of how the system is functioning and we expand on the social aspects of the model.

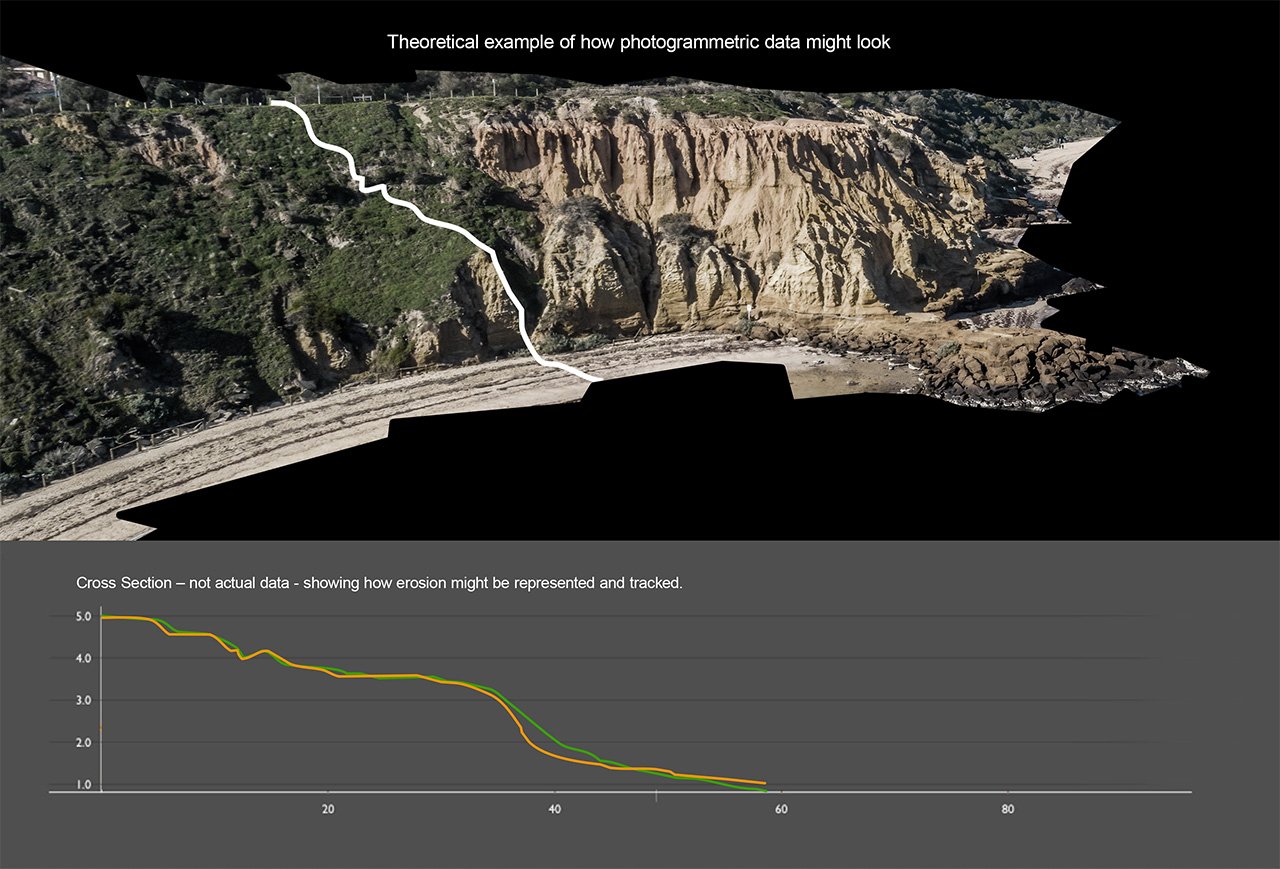

The idea is to develop a picture of how the Bay currently functions and how various Bay users are already affected, both positively and negatively (see image, above).

This model is presented back to our community in a way that everyone can view and understand. For the first time, local people will be able to visualise their own relationship to the Bay and how our activities can both help and hinder the economy. Results will be public and open source.

Step 4.

Scientific surveys

Together with baseline surveys of our own (these start at the beginning of the program) we will co-design additional science work with the community. This ensures that we address gaps in knowledge that the community itself has identified.

For example, there are likely to be many important community values for which data has never been collected. This will be needed to finalise the model and we will help design these, so the knowledge gaps can be filled on the community’s behalf.

Step 5.

Evaluation

At this point the model will be filled with knowledge from many abundant and co-validated sources. It will represent one of the most comprehensive overviews of how the Bay works that’s ever been done. We will be able to identify:

threats and pressures of greatest significance;

priorities for action that are the most important for the community as a whole (socially prioritised); and

socio-ecological pathways where action to address these priorities, is likely to have the greatest effect.

The benefits of this approach are that recommendations for policy change, monitoring and management, can now be focused where they make a difference and represent value for money. They are also guaranteed to be the parts of most importance to the community as a whole.

The final stage is to manipulate the model by dialling pressures and threats up or down, until optimal solutions are found, that create the best outcome for everyone.

The aim is to rebalance our decisions with natural processes, thereby protecting life support services and boosting the economy.

Next steps

During the Evaluation stage, we will have identified governance obstacles and enabling conditions needed, before community wishes can be realised.

This part of the process is critical. The majority of programs that time to create change, don’t identify the obstacles. These can be the way we behave or government policy. Recall that our overall behaviour today is how we’ve grown a strong economy over the last few decades. Now we need to make change happen, we have to work out how to disentangle and rebuild policies based on what our community needs today.

This becomes a process of working together, to translate intentions into reality. This isn’t a rapid process but it’s achieveable only if we have already done the steps above.

The team who are helping deliver this program for the community will be helping us put these outcomes into a community-owned stewardship plan. They will then be taking these measures to government, to lobby for changes in policy, so the community’s outcomes are more likely to be achieved. This step has been missing from many such projects before and it’s why this program is different, and likely to lead to greater success.